Friday, April 27, 2012

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

Errors in the Use of Words: Mistakes of Purists from 1905

In The Art of Writing & Speaking the English Language (The Old Greek Press, 1905), Sherwin Cody refers to his pocket-sized book as a book of quick study rather than an exhaustive reference. So rather than correctly and strictly adhering to rules, this book aims to "add knowledge of the differences and shades of meaning, fine distinctions in the values of words, and variety of expression."

Through his book, Cody says he has "tried to lead the student to a nicer discrimination in the meanings and values of words in common use, and to avoid making a pedantic prig of him. While purity of language is greatly to be desired, nothing is more amusing than to read the tirades of the purists."

He continues, "There is a vast amount of rubbish afloat about good and bad usage, and I know no class of pedants more disagreeable than those who set up to correct the English of everybody else. I want to make language freer more accurate, and more expressive, not stiffer, drier, and deader. (How the 'stiffs' will carp at that word 'deader'! Let them!)"

In the late 1800s, every time a comprehensive/official/correct book by one of the purists came out, a host of fellow purists waited in line to tear it down. Cody said that it got to be so that "it became dangerous to open one's mouth."

(This sentiment has a modern-day ring to it, doesn't it?)

He then goes on to say that this is all wrong. "Language is for the purpose of expression, and it is full of elisions, substitutions, comparisons suggested, and words used in certain phrases with meanings purely idiomatic and unexplainable. If we frighten ourselves with a bugaboo of errors, we shall become stiff and awkward."

Are you nodding your head as empahtically as I am?

As every writer and reader knows, such specious arguments about language still abound. We're told that language should not be like this, but should be like that.

For example, in Cody's day, he said that they were told that a sentence should not end with a preposition. But Cody says, "Throwing the preposition to the end is one of the most thoroughly established idioms of the language."

In 1905, Cody said that it is alright for it to be so. But aren't we still fighting that battle to this day? So which rules are our modern-day pendants referring to when they say that it is incorrect usage of grammar for the sentence to end in a preposition? Eighteenth century ones?

Write back:

1 comments

Posted on:

4/25/2012 03:47:00 AM

![]()

Labels: Humor, Research: Words

Copyright 2006–2023 Keira Soleore (keirasoleore.blogspot.com)

Monday, April 23, 2012

Bookish Meme 2: Reading Habits & History

Credit for the original set of questions goes to Janga of Just Janga. I've changed/deleted some of the questions that were already covered in my March Bookish Meme post.

Credit for the original set of questions goes to Janga of Just Janga. I've changed/deleted some of the questions that were already covered in my March Bookish Meme post.

What were your favorite childhood books?

There are so many to choose from, but basically, anything by Enid Blyton, a British children's author from the 1940s. My first book by her was Merry Mister Meddle, a book about a little man who always got into trouble. My first foray into mysteries was via her The Mysterious Bundle, a book featuring a group of children called the Five Find Outers who live in a small village and are smarter than the local constable. Her farm books, such as Mistletoe Farm and her boarding school books, such as the St. Clare ones will be ones I won't ever forget

What are you reading right now?

The Devil's Delilah, a traditional Regency by Loretta Chase

Charlotte Web, a children's tale by E.B. White

Have your reading habits been affected by the Internet?

Oh, absolutely. Most of my discoveries about authors have been due to chats on romance blogs and boards and on Twitter. Sometimes, the recommendations are just for a book, and I get hooked on to the writing so much that I buy the author's entire backlist. Sometimes, it's a particular book that comes highly recommended by trusted sources that goes on my keeper shelves and that I return to over and over again

What is your reading comfort zone?

I mostly read historical romance fiction and historical fiction. I also read a limited number of contemporary and western romance fiction novels. Lately, I have been challenging myself to read books by male authors, more nonfiction, and non-romance fiction

What makes a book a keeper for you?

I have to love the characters, first. If the book is set in medieval times or Georgian-Regency times, I'm already half-way to liking it. A plot that's different from the norm, even while it works with the basics of the norm. And oh, the writing. I don't like Hemmingway-style brevity, nor Annie Proulx-style choppiness, but neither do I like Woodiwiss-style purple prose—overly lyrical and chock-full of metaphors are tiresome. I go for being able to paint an original picture with precisely chosen colors. And of course, if the book is by an author whose other books I have loved, I'm predisposed to liking the current book, too

What will inspire you to recommend a book?

Characters, story, writing

How often do you agree with critics about a book?

Not often, it would seem

How do you feel about giving bad/negative reviews?

I rarely comment on books, and the ones I do so are ones I have liked. I go for my opinion, not for a fair and unbiased review

What is the most intimidating book you've ever read?

The Fountainhead by Ayn Rand. I despised the protagonist, architect Roark. And yes, I finished the doorstopper

How often do you not finish a book you begin?

These days, less and less, and not because I'm dogged about slogging to the end, as I was in my salad days. In fact, I'm far more discriminating now. However, for the last couple years or so, I've only read books by auto-buy authors or those recommended by a select few friends and acquaintances. So my hit rate is much higher

What's the longest you've gone without reading?

Perhaps 2–3 days when I was sick. I've always read, whether it's fiction, nonfiction, or textbooks

What's the greatest number of books that you've read in a day?

Two romance fiction books

What's your favorite film adaptation of a novel?

By film adaptation, I mean a new take on the original book, a new film based solely on the original book. So Clueless based on Emma by Jane Austen is a shoe-in for me

Can you think of a book you didn't expect to like but did?

There are many such books, but a recent one that comes to mind is the one I read last year: Welcome to My World by Johnny Weir

What books have you read most often?

The St. Clare and Mallory Towers book series by Enid Blyton

The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas

Pride & Prejudice by Jane Austen

These Old Shades by Georgette Heyer

Devilish by Jo Beverley

What book do you have the most copies of?

Pride & Prejudice by Jane Austen is the only one. I don't have even two copies of any other books

What book have you tried but failed to finish most often?

I have always loved Tolstoy's short stories, but pray-god, not War and Peace. I want to like it, but I can't even get a quarter of the way through it

Write back:

0

comments

Posted on:

4/23/2012 04:01:00 AM

![]()

Labels: Leisure: Reading

Copyright 2006–2023 Keira Soleore (keirasoleore.blogspot.com)

Friday, April 20, 2012

Picture Day Friday: Victorian Food Art

Thanks to Loretta Chase for bringing Edible Artistry to my attention.

A basket of flowers made in fruit-flavoured water ices

According to Ivan Day of Food History Jottings: "By the 1880s, this highly ornamental style of cuisine was being practiced by home cooks as well as professionals. Cookery schools like that of Mrs Agnes B. Marshall in Mortimer Street, London were not only teaching housewives and domestic cooks how to make these spectacular dishes, but also sold you the necessary moulds, cutters and other equipment."

Mrs. Marshall sounds like the Victorian version of Jamie Oliver or Rachael Ray, doesn't she?

Ivan Day is an independent social historian of food culture and also a professional chef and confectioner.

Write back:

0

comments

Posted on:

4/20/2012 04:06:00 AM

![]()

Labels: Research: Culinary

Copyright 2006–2023 Keira Soleore (keirasoleore.blogspot.com)

Wednesday, April 18, 2012

Redefining eBooks: Just Plain Text or a Richer Experience

The Department of Justice has accused the top six book publishers of New York City for colluding with Apple to set the price for eBooks at $12.99 to $14.99. Amazon wanted to set the price at $9.99, which caused so much outrage among the publishers that they sought a new kind of partnership that believed what they believed was the right price for eBooks, namely, Apple.

Publishers and booksellers think that the price of an eBook should be somewhere between the price of a mass market paper back (MMPB), which currently hovers around $7.99, and a trade paperback (TPB), which is around $14.99. They believe that this way, the loss in eBook version of hardcovers (HC), which are usually around $25.99, is recouped in eBook version of MMPBs.

Consumers, on the other hand, think that the price of eBooks is incredibly hyped. They believe that the price should be around $5.99 (some even suggest $3.99). The thinking here is that there are no printing, storage, and shipping costs associated with eBooks. Yes, there are production costs, such as editorial and artwork, but those are shared with the print versions. So the price of the book should be lower than the price of a MMPB.

In my opinion, the reason behind this assumption by consumers is because an eBook is nothing more than a digitally available file of the text that can be found in the pages of a MMPB.

You could argue that a HC and MMPB versions of the same book (the latter of which is usually released a year after the former) have the exact same text. That is true. However, the HC provides the value-add of, what hardware electronic manufacturers call "form factor." The HCs come with dust jackets, end papers, good quality paper, and a satisfying heft and look on the bookshelf. This justifies their price.

Similarly, a TPB shares the same text as the MMPB version of a book, but again "form factor" comes into play: the height, the slimness, the texture of the pages, the book and page design, and for some, the image of reading "literature," since most of non-genre books are published in TPB.

The advantages of a MMPB over HC and TPB is ease of use: holding it up, reading in bed/bath/beach, and carrying it around.

An argument could be made that an eBook similarly has a very different form factor from a MMPB, with easy-to-read text on a light eReader that allows searching within the text. So the eBook should be able to command it's own niche for pricing.

From a consumer's point of view, however, the purchase of the eReader with its host of features, is completely decoupled from the purchase of a book. An eReader allows the reader to read innumerable books, not just one particular book, meaning, the eReader reading experience is not tied to the book being read. So the eBook is once again reduced to mere text, at which point, it's no different from the lowest print version of the text, namely the MMPB.

What completely astounds me is that in all these shenanigans in deciding on the price for an eBook nobody seems to have given one thought to innovating the content of an eBook.

Instead of trying to pass off the same-old, same-old as the new new, why not truly provide something new? Give the reader a reason (or a dozen) to pay more for digital content. Provide them with features on the digital version that they will not find in any of the print versions, thereby, redefining the "form factor" of an eBook. This might induce people to pay a premium $12.99 for it or to own multiple copies of a book (print and electronic).

What do I mean by extra features? This is not just more text, such as deleted scenes, interviews, author's notes, or readers' guides, added to the back of the main book. This could easily be added to print books, too, so this is nothing cool.

Let's choose the example of a historical novel. What if an architectural detail, the name of a famous painter, a seminal event, etc. were hotspots in the story? If the reader were to tap on it, a balloon would pop up with detailed information, including a picture if appropriate, about the topic. The author has already done the research and could easily code the text of her manuscript with these tidbits, which could be stripped from the production of print books, but highlighted in the electronic versions.

Publishers could host additional content on their websites, provided by the authors, hot-linked to from within the eBooks, such as musical pieces, an online viewing of a museum's art gallery, recipes of historical foods, and so on. For a nonfiction book, the bibliography could be hyperlinked to the actual papers and books on the Internet. The website tie-in would give the publishers another way to brand their eBooks.

What this does is gives the reader an incentive to plunk down their hard-earned money for something new and different, rather than an entitlement demand from publishers for the same text. What it also does is that it respects and leverages the electronic medium to change the conversation about books. Now a book is no longer passive text on the page, but an interactive reader experience.

It's time for the publishers to forge ahead into the 21st century and own the new medium instead of vainly trying to confine it to the standards of the medium from the 15th century.

Write back:

0

comments

Posted on:

4/18/2012 04:39:00 AM

![]()

Labels: Business: PublishingIndustry

Copyright 2006–2023 Keira Soleore (keirasoleore.blogspot.com)

Monday, April 16, 2012

A Subscription-Based Circulation Library Plan for eBooks

In the wake of the Department of Justice suing the Big-6 book publishers and Apple for colluding to set prices for new eBooks in order to cut Amazon out of the running, I've been thinking that someone somewhere needs to figure out how to lend eBooks out to people.

Now, OverDrive and a few public libraries have been trying to do just that, but the list of choices on OverDrive is thin. Not all publishers believe that eBooks should be lent out through libraries. Also, publishers are not convinced that eBooks should be allowed to be treated just like print books by the library, i.e., the libraries buy a print book once and then it's free in perpetuity (or till it falls apart) for the readers.

The publishers feel that this would be a loss of revenue for them for eBooks and have tried to come up with draconian rules as to the number of times an eBook can be lent before the library must pay for a new license to the same book. Libraries are strapped for cash and are used to paying once for a print copy and then never again, so this renewing of licensing fees doesn't fly with them.

OverDrive's books are also locked up by Digital Rights Management (DRM), because the publishers are afraid of the books being pirated if they're open. (If you visit sites like this, you quickly realize that it's not terribly difficult to strip off DRM, so why bother with DRM in the first place?)

Addressing the first concern of the publishers that they're not getting enough money for their product, I have an idea that's a combination of what Netflix and public libraries do, in the form of the old-fashioned Regency-era circulation library.

Say, a brand new company comes along, with the truly innovative name, eBook Circulating Library (ECL). It charges customers a monthly subscription fee. For that fee, a reader can check out, say, three books at a time. Every time, they return a book, they can borrow one more, and so on, for an unlimited number of books every month.

Each book can be borrowed for one month and can be renewed once for another month. If a reader fails to renew or return the book on the due date, then after, say, two reminders and a grace period of, say, one week, the reader is charged the full price of the book. Alternately, the book expires and is deleted from all devices that the reader copied it to. In either case, the book is then taken off the reader's list of checked-out books, and the reader can borrow other books.

Now, these eBooks are DRM-free with no geographic restrictions, so readers can read them on the eReader of their choice.

Each book is tagged with a unique activation code like boxed software from say, Microsoft. So when the reader first opens the book on their reader, the device sends the code back to the ECL company informing them that this particular copy was opened by this particular reader on this particular device on such-n-such date.

If you copy the book to your other six devices or lend it to your close friend, each time, the copy is opened on a new device, the activation information is sent to ECL. However, this eBook can be read on only a total of, say, ten devices, and no more than that during the current borrow/renew period.

The hitch in this idea is that the books still need to be DRM-free. But, if every reader is paying a fee for the privilege of borrowing copy of the eBook, then perhaps the possible loss of a few to piracy can be shrugged off by the publishers.

What problems do you see with this idea?

Write back:

0

comments

Posted on:

4/16/2012 04:46:00 AM

![]()

Labels: Business: PublishingIndustry

Copyright 2006–2023 Keira Soleore (keirasoleore.blogspot.com)

Friday, April 13, 2012

Picture Day Friday: Little Free Library

The mission of Little Free Library is to promote literacy and the love of reading by building free book exchanges worldwide.

It all started three years ago, when "Todd Bol came up with an idea to remember his mother, a teacher who had loved books and encouraged people to read. At his home in Hudson, WI, he built a box, made it waterproof and filled it with books. It looked like a miniature one-room schoolhouse, with a sign underneath that said 'Free Book Exchange.' Bol put it on a post outside of his house and invited neighbors to take a book, and return a book. 'People of all ages, men, women, kids came up and just loved the library,' Bol said. 'They got excited and they started coming up to me saying, "I’ll build one, do you need books?"'" And the idea took off. Now there are Little Free Libraries in at least 28 states and six countries. (More coverage on this story is HERE.)

Write back:

0

comments

Posted on:

4/13/2012 04:10:00 AM

![]()

Labels: Leisure: Reading, Research: Education

Copyright 2006–2023 Keira Soleore (keirasoleore.blogspot.com)

Wednesday, April 11, 2012

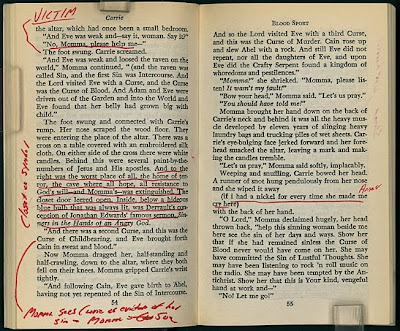

Do You Write In The Margins?

There are people who are vehemently opposed to defacing books, inside and out. Many take great care not to crack the spines of mass market paperbacks or dent the dust jackets of hardcovers.

There are people who are vehemently opposed to defacing books, inside and out. Many take great care not to crack the spines of mass market paperbacks or dent the dust jackets of hardcovers.

Me? I like to write margin notes. I highlight relevant lines. My paperbacks don't have uncreased spines. My dust jackets might end up with creases and minute tears. About the only thing I will not do is dog-ear the pages.

Looks like I am in ancient company. Even those monk scribes who laboriously worked for months on a single illuminated manuscript, tended to leave margin notes.

The following, unintentionally humorous, GEMS come from the spring 2012 issue of Lapham's Quarterly, entitled Means of Communication. Thanks to Brain Pickings for bringing them to my attention.

The parchment is hairy.

The parchment is hairy.

Oh, my hand.

Thank God, it will soon be dark.

Writing is exessive drudgery. It crooks your back, it dims your sight, it twists your stomach and your sides.

As the harbor is welcome to the sailor, so is the last line to the scribe.

Now I have written the whole thing: for Christ's sake give me a drink.

My justification for marginalia comes from How to Read a Book by Mortimer Adler (1940).

My justification for marginalia comes from How to Read a Book by Mortimer Adler (1940).

"When you buy a book, you establish a property right in it, just as you do in clothes or furniture when you buy and pay for them. But the act of purchase is actually only the prelude to possession in the case of a book. Full ownership of a book only comes when you have made it a part of yourself, and the best way to make yourself a part of it—which comes to the same thing—is by writing in it."

"Reading a book should be a conversation between you and the author. Marking a book is literally an expression of your differences or your agreements with the author. It is the highest respect you can pay him."

Does that make you want to take a pen to your books?

Write back:

2

comments

Posted on:

4/11/2012 04:10:00 AM

![]()

Labels: Leisure: Reading, Research: Books, Research: FineArts

Copyright 2006–2023 Keira Soleore (keirasoleore.blogspot.com)

Monday, April 9, 2012

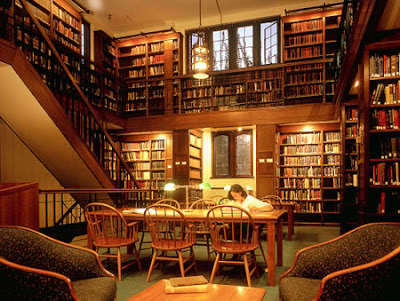

My Home Library

Whenever I meet new people or visit people's houses, books always seem to crop up in the conversations. And I find I'm unfailingly interested in people's book collections. What someone reads tells me a lot about the kind of person he or she is. Assuming as my blog reader, you're likewise interested in my home library, here're a few questions I posed to myself and answered herein.

Where is your home library housed?

The library is split up into three pieces. Adult fiction is in the study upstairs, children's books actively being read are in a bedroom upstairs, and the rest of the collection (nonfiction, children's books, coffee-table books, etc.) are all in the library downstairs.

What is the system of book organization?

The fiction is alphabetized by author only and unsorted within each author section. The bookshelves consist of smallish rectangular boxes, each alphabet gets one or more boxes, depending upon the number of books. The children's books, upstairs, are organized by author only and not alphabetically. The children's books, downstairs, are completely unorganized, except for board books on one shelf and the rest on another. The nonfiction is organized thematically, for example, sciences, travel, foreign languages, cookbooks, etc., but unorganized within each category.

Approximately, how many books do you own?

~2000

What was the first book you were gifted with?

The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, translated into English by Katherine Woods and published by Harcourt, Brace & World in NYC in 1943. My mother owned it before she was married, and she gave it to me when I was born.

Which books did you buy first?

Four books in 1979:

—The Mutiny of Board H.M.S. Bounty by William Bligh, adapted by Deborah Kestel and pubbed by Playmore Inc. under arrangement with Waldman and Son, NYC (1979)

—Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There by Lewis Carroll, pubbed by Piccolo Pan Books, London (1977)

—Man in the Sky: the early years by Althea Braithwaite, pubbed by Colourmaster International, Huntingon England (1972)

—The Littles Go Exploring by John Peterson, pubbed by Scholastic (1978)

Which is the book with the oldest copyright in your collection?

The Cousins by Maria M'Intosh is a children's book pubbed by George Routledge and Sons of Ludgate, London. The copyright page has been lost, but the last known owner was one Emily P. Mason. Her name's inscribed inside along with the date January 1, 1882. I bought it from Barter Books in Alnwick, Northumberland, England on June 26, 2002.

What are your most unusual books?

—Seven Poems by Hans Christian Andersen, translated into English by R.P. Keigwin, published by H.C. Andersen Hus in Odense, Denmark in 1955. I acquired this collection from the Andersen House in Odense on July 10, 2002. In the western world, Andersen is not known for his verse, though he wrote quite a bit in his salad days, including one when he was but a schoolboy. A few of his poems have been set to song and are very popular as national songs.

—Why I Live On The Mountain is a collection of thirty Chinese poems from the Great Dynasties, translated by C.H. Kwôck and Vincent McHugh, with calligraphy by John Way, and pubbed by Golden Mountain Press, San Francisco in 1958.

Which is the shortest book, in terms of number of words?

Baby Face by Dorling Kindersley (2002) has 18 words.

Which is the longest book, in terms of number of words?

I have a hardcover collected edition of 566 pages by Wings Books, Random House (NYC, 1991) of three of Dorothy Sayers books: Strong POison (1930), Have his Carcase (1932), and Unnatural Death (1927). (Aside: Sayers's full name is Dorothy Leigh Sayers Fleming.)

Are you a hardcover book collector?

I haven't gone out of my way to collect hardcover books. If the book I'm interested in buying only exists in hardcover, then I'll buy it. Otherwise, whatever is the cheapest edition, gets my money.

Has your library grown steadily since your first purchase?

Not at all. My collection was tiny through all my schooling and college years—I borrowed heavily from friends and libraries. It's only when I got my first full-time job that I had the spare cash to purchase books. Even then, I read far more from the library than I bought from the bookstore. It was finally when I became an aspiring writer of historical romance fiction that I started collecting books in earnest. I needed books on the craft of writing, for research, and as examples of writing in my sub-genre. In addition, I felt that if I expected others to buy my future books (when—not, if—pubbed), I should be doing the same thing for other authors.

Write back:

2

comments

Posted on:

4/09/2012 04:09:00 AM

![]()

Labels: Leisure: Reading

Copyright 2006–2023 Keira Soleore (keirasoleore.blogspot.com)

Friday, April 6, 2012

Picture Day Friday: Book Crate Bed

Write back:

0

comments

Posted on:

4/06/2012 01:05:00 AM

![]()

Labels: Leisure: Reading, Research: Interiors

Copyright 2006–2023 Keira Soleore (keirasoleore.blogspot.com)

Wednesday, April 4, 2012

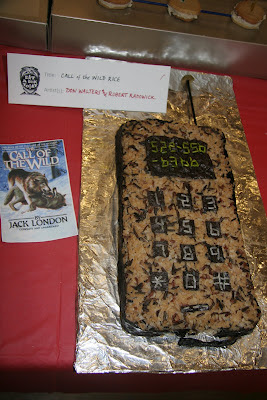

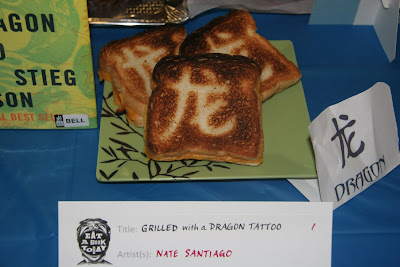

Seattle's Edible Book Festival

"Eat a Book Today" is the motto of The Edible Book Festival "celebrating books and food and the people who love them." It is organized by the Seattle Center for Book Arts. This year was the seventh annual event on March 31.

"Eat a Book Today" is the motto of The Edible Book Festival "celebrating books and food and the people who love them." It is organized by the Seattle Center for Book Arts. This year was the seventh annual event on March 31.

If you make and take an entry to the event, entrance is free, but prior registration is required. If you're only going to watch (and eat!), then there's a fee of $10 per person.

Schedule of Events:

• 11:00 to 12:00 Entries accepted, installed, photographed

• 12:00 to 1:30 Public viewing and voting for Best in Show

• 1:30 Celebrity Judges award prizes

• 2:00 Edible Books eaten with tea, coffee, milk

Categories:

• Most Pun-derful

• Most Drop-dead Gorgeous

• Most Delectably Appetizing

• Best Young Edible Artist (K-12)

• Best in Show

Instructions:

"Create and bring a piece of edible art related to books: it can pun on a title, refer to a scene or character, look like a book (or a paper, a scroll, etc.), or just have something to do with books. Whatever the inspiration—it must be edible. Think of brainy, beautiful, silly, clever, and tasty transubstantiations of books we love into treats we eat! Every type of book—children's classics, detective novels, biographies, fiction and non, poetry, short stories—should be sculpted from a smörgåsbord of foodstuffs. Supply a placard with the title of your piece and your name." Also include the book you're riffing of.

The following images are all photographs taken by me. Commentary follows each picture. Click on the image to get a bigger, better view.

Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

Le Petit-Four Prince from Le Petit Prince or The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Oh, those poor bleeding arms in Farewell to Arms by Hemmingway

Delicious panna cotta in Drawing on the Right Side of the Brainna Cotta from Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain by Betty Edwards

Harry Potter and the Deadly Challah-ohs

Call of the Wild Rice from Call of the Wild by Jack London

The magnificient breaded dragon is holding sway over cheese in The Girl with the Dragon Fondue

Check out the hellfire in Satanic Purses from Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie

Grilled with a Dragon Tattoo

The pièce de resistance of the show: Quoth the Raisin "Petit Four" from The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe.

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore,

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

`'Tis some visitor,' I muttered, `tapping at my chamber door -

Only this, and nothing more.'

[.....]

Quoth the raven, `Nevermore.'

Write back:

0

comments

Posted on:

4/04/2012 03:20:00 AM

![]()

Labels: Leisure: Art, Leisure: Reading

Copyright 2006–2023 Keira Soleore (keirasoleore.blogspot.com)

Monday, April 2, 2012

Sir Walter Scott and the Modern Novel

[This is a long post.]

The quotes in this post are from Beacon Lights of History: Great Writers by John Lord (©1896). The edition I read was published by WM. H. Wise & Co. in 1921. It's an erudite biography with quotes, remarks, opinions, and facts all delivered mostly in a conversational tone, but sometimes with extremely dry asides that are, maybe unintentionally, hilarious.

"Perhaps one test of a great book is the pleasure derived from reading it over and over again. Measured by this test, the novels of Sir Walter Scott are among the foremost works of fiction, which have appeared in our world."

Sir Walter Scott is said to be the father of the modern novel and the father of the historical fiction novel. His books were termed Romances, not in the popular meaning of romance novels, but rather stemming from the French word roman, meaning novel.

John Lord in his Beacon Lights was openly admiring of Scott: "He who could charm millions of readers, learned and unlearned, for a quarter of a century, must have possessed a remarkable genius."

Childhood

A trip to his grandmother's house in the Border Lands of Scotland in his early childhood, introduced Scott to many of the tales, ballads, and legends that went on to become a lifelong passion for him. "As a youth, he devoured everything he could find pertaining to early Scottish poetry and romance, of which he was passionately fond. he was also peculiarly susceptible to the beauties of Scottish scenery..."

By the time, Scott graduated from University, he was fluent (in literary and colloquial) French, Italian, and German and literary Latin. In addition, he was a dedicated student of philosophy and Scottish Law (current and antiquarian). He'd written verses in Latin and English and translated books from German and Italian into English. Despite this, Lord wrote, "On the whole, he was not a remarkable boy, except for his notable memory (which, however, kept only what pleased him), and his very decided bent toward the poetic and chivalric in history, life, and literature."

Personality

"Great lawyers and great statesmen are rarely so egoistical and conceited as poets, novelists, artists, and preachers."

But according to Lord, Scott was sweet-tempered, merry, generous, cheerful, witty, modest, unpretentious, bright, and well-beloved. He was also a brilliant storyteller and a good sportsman, yet he was peremptory and pertinacious in pursuit of his own ideas. Admist great fame and prosperity, he never lost his "intellectual balance," his habitual modesty, or his work ethic.

"He praised all literary productions except this own. His most striking peculiarity was his good sense, keeping him from all exaggerations, which was always offensive to him."

Profession

Scott was a solicitor by day and a writer by night. He assiduously attended to his duties in the Courts, but "No man can serve two masters." Scott's heart was not in lawyering, but in writing about the beauty of Scotland—the land, its people, its culture, and its politics.

Prodigious Interests

Other than poetry and long fiction, Scott wrote short story collections. His nonfiction efforts, included writing: reviews, essays, biographies, histories of Scotland and France, political pamphlets, dramas, religious discource, introduction to divers work, encyclopedia entries, book-length translations, and editing of collections of other authors.

In addition to his literary pursuits, many other things called upon his time: five children, the law, a vast correspondence with famous people with the postage itself exceeding 150 pounds per anum, an avid interest in reading, a passion for vigorous hiking in the Scottish countryside, a yen for traveling, an outpouring of love overlooking the building of a castle mansion at his beloved Abbotsford and the cultivation of its 1,200 acres of land, and cheerfully entertaining a constant stream of guests (friends and curiosity-seekers alike).

"How Scott found the time for so much work is a mystery."

Poetry

Scott started writing poetry as a young boy of five and continued writing poems and ballads throughout his schooling. He gained middling fame for them. However, it was finally in 1805, when his first original poem The Lay of the Last Minstrel sold 50,000 copies that he became truly famous in the British Isles. In 1808, his poem Marmion: A Tale of Flodden Field was "received by the public with great avidity and unbounded delight," and eventually sold nearly 50,000 copies. Scott continued to write and sell poetry while engaged in his fiction pursuits.

Prose

At the time Scott decided to try his hand at prose fiction, it was still considered aesthetically inferior to poetry and especially to the classical epics or poetic tragedies. So in an astute move, Scott published his first novel Waverley (1814), dealing with the Jacobite rebellion of 1745, anonymously to test the waters for the reception of such reading material. Despite his unacknowlegment of the novel as his, it was widely known that he was the author. It was so popular, that in 1815, he was given the honour of dining with George, Prince Regent, who wanted to meet the 'Author of Waverley.'

In the next fifteen years, Scott wrote at the cracking pace of nearly three novels a year—all were Scottish, most of them historical. His novel Guy Mannering (1815) sold out its first edition on the day of publication. Antiquary (1816) sold six thousand copies in six days. Rob Roy (1817), a portrait of the great Scottish hero, sold out its edition of 10,000 copies in two weeks. And so on.

Of the book Old Mortality from the series Tales of My Landlord, Lord had this to say: "It is justly famous for it was the precursor to [his] brilliant historical romances. He made romance instructive, rather than merely amusing, and added the charm of life to the dry annals of the past."

Here then is the definition of a historical fiction novel, according to Lord: "Scott's ability to 'toil terribly' in accumulating choice material and then, fusing it in his own spirit, to throw it forth among men with this 'hurried frankness' that stirs the blood, was the secret of his power. Fashion in these times delights in what is obscure and difficult to understand, as if depth and profundity must necessarily be unintelligible to ordinary readers." However, Scott participated in his writings in full enthusiasm, a feeling, which was "like sunshine upon a landscape, lighting up every beauty and palliating, if it could not hide, every defect." [Text in single quotes is Scott's own opinion of his writing.]

Scott was the first English-language author in the early 1800s to have a truly international career in his lifetime with many contemporary readers in Europe, Australia, and North America. His prolific output and the popularity of it made him a shoo-in for a baronetcy in 1820. Scott was the first purely literary man to be made a baronet.

He died in September 1832. By 1847, Scott's literary work had produced as profits to Scott (during his lifetime) and his trustees (after his death) a total of $2.5 million from Britain alone.

Of Scott's literary climate, Lord wrote: "The most supremely fortunate writer of his day came to a mournful end, notwithstanding his unparalelled honors and his magnificient rewards." In contrast: "When we remember the enthusiasm with which the novels of Scott were at first received, the great sums of money which were paid for them, and the honors he received from them, he may well claim a renown and a popularity such as no other literary man ever enjoyed." [Lord was writing this in 1896.]

Lord further wrote: "[His novels] have some excellencies which are immortal—elevation of sentiment, chivalrous regard for women, fascination of narrative, the abscence of exaggeration, the vast variety of characters introduced and vividly maintained, and above all, the freshness and originality of description, both of Nature and of Man. What is simple, natural, appealing to the heart rather than to the head, may last, when more pretentious poetry shall have passed away."

Walter Scott, however, had this to say about immortality: "Let me please my own generation and let those who come after us judge of their facts and my performance as they please; the anticipation of their neglect or censure will affect me very little." Spoken like a true commerical fiction novelist with no aspirations to pretentious literary fiction greatness.

Write back:

0

comments

Posted on:

4/02/2012 03:26:00 PM

![]()

Labels: Business: Authors, Research: LiteraturePoetry, Research: Regency

Copyright 2006–2023 Keira Soleore (keirasoleore.blogspot.com)